Parasite by Mira Grant explores a near future in which medical tech giant SymboGen convinces the world to become human hosts to genetically modified tape worms. What could possibly go wrong?

On my list of Most Terrifying Things are such horrors as abused apostrophes and Rush Limbaugh’s hypnotic, bigoted radio voice, but right up there near the top are also zombies and parasites. Author Mira Grant managed to tackle both those subjects in her novel Parasite, the first installation of her Parasitology series, which ends up being closer to a mash-up of Animal Planet’s Monsters Inside Me and Resident Evil. Not as terrifying as Rush Limbaugh misusing apostrophes, but much more enjoyable.

Grant’s particular brand of terrifying things starts in the mind of Sally Mitchell, a young woman who beats all odds and wakes up from an car accident-induced coma. The only problem is she can’t remember a thing. As Sal develops, her family and friends comment again and again that she’s a completely different person. Gone is the bitchy, selfish, temperamental Sally. Sal is kind and inquisitive, respectful to everyone, and deathly afraid of driving in cars. Sal’s life was saved by a medical miracle: SymboGen’s genetically modified tape worm, D. symbogenesis, which cures everything from pet allergies to cancer. Six years after Sal’s accident, she is relearning the way to be human and navigating her celebrity as the girl whose life was saved by a worm. But when other D. symbogenesis hosts start falling prey to an epidemic of sleepwalking, Sal becomes suspicious and tries to uncover the dangerous secrets of SymboGen.

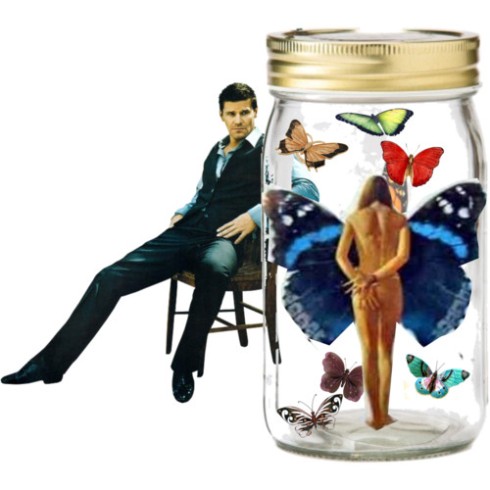

Tape worms and other parasites are creepily pretty in artful photos like this. They lose their appeal when you imagine them wrapped around your brain.

Sal narrates as a story of her medical miracle evolves into a story of political intrigue, conspiracy, and deadly, sleepwalking, worm-controlled zombie people. Remember that Sal woke up from a coma six years previous and relearned everything that makes a human being human. She makes a point to express her trepidation with the English language, and she often comes across as awkward or clumsy with her speech in dialogue. But her running, first-person monologue is perfectly formed, descriptive, witty at times, and sometimes downright lyrical. This isn’t the voice of someone forced to use an adult brain to learn a brand new language. This is the voice of a snarky, educated, well read author of multiple novels.

It’s a rare case when I wish for a little more distance from a narrator, but the more I learned about Sal, the less I appreciated her. Her intelligent narration made her seem fraudulent when she presented herself as a bumbling, naïve victim in her interactions with other people. The lack of consistency in Sal’s character (in addition to her banality in general) hamper what would have otherwise been an interesting story.

But wait! There’s more. In case Sal’s blasé character profile doesn’t do it, the silly plot progressions could certainly deter a reader from picking up this novel. I can’t get over the fairly silly plot progressions. After a near apocalyptic run-in with sleepwalkers on a highway, Sal is immediately grounded for a week her parents for leaving the house without permission. After Sal learns that the horrifying sleepwalking epidemic are truly sentient, genetically modified tape worms taking over their slaver hosts, a series of cliché revelations ruins it all. At other times, plot holes or straight up plot errors cripple the narrative flow just as the story starts picking up pace.

As far as icky worms controlling their human hosts go, Parasite is by no means the first to go there. My favorite tummy worms are Stargate: SG-1‘s Goa’uld–the worm babies of an alien race that use humans’ easily repaired bodies as hosts.

A friend of mine enjoyed Grant’s Parasite–a friend whose opinion I respect and whose reading tastes I trust–a friend who was able to overlook what may seem like small criticisms in Grant’s writing style, character development, and plot progressions. My review might be relatively harsh for a novel that is shortlisted for the 2014 Hugo Award, but I stand by my two-star Goodreads rating. For a book that is acclaimed and could beat out such a gem as Ann Leckie’s Ancillary Justice for the Hugo, Parasite falls grossly short of my expectations. The novel had some potential, but the execution was poor. Even the concept was disappointingly derivative. I wish the best to Mira Grant, but if Parasite wins the Hugo, I will pout for days and write something inflammatory on Twitter.

Read this book if … you’re a sucker for zombies and morbid apocalyptic novels. Read it if you’re the one who clicks on that link to BuzzFeed’s “10 Grossest Something Something” article. Read it if you’re not going to focus on logic or details, and you’re just along for the ride.

Don’t read this book if … the booming zombie genre gives you a case of the Disgruntled Sighs. Grant isn’t the first one to make zombies via little bugs in your brain, and Parasite doesn’t try too hard to be original in any other way. Like me, you may get distracted by the flaws in narrative logic, and there isn’t too much to draw your attention back on track.

This book is like … The Shining Girls by Lauren Beukes, which tells a very different story about a woman who is a survivor, a survivor with a terrifying burden that leads to incredible mysteries. Kirby Mazrachi barely survived the vicious attacks of a murderer, and she spends her life trying to exact justice. With a much stronger protagonist and sounder sci-fi themes, The Shining Girls

Mira Grant, whose actual name is Seanan McGuire, really likes zombies, and probably has a thing for sharp, stabby objects.

What is your favorite kind of zombie? George Romero zombies? Resident Evil zombies? Shaun of the Dead zombies?