A few recent reads inspired me to make a list of some great survival stories. Many writers attempt to capture the age-old struggle against Nature’s tempests, but only a few succeed. The list below are some favorites of mine–new and old–that I hope you will enjoy! In the comments, let me know your own favorite books of humanity’s battle for survival!

FIVE

Serena by Ron Rash

There’s something about my cozy urban life and redundant desk job that makes me want to read books of perilous adventure. In Ron Rash’s Serena, I found a title character who is in almost every way my opposite. Serena Pemberton and her husband are lumber barons in 1920’s North Carolina. They battle nature’s lethal touch and their partners’ unfaithfulness with equal fervor, doling out their cold-eyed vengeance left and right. Serena is the story of a character more like a force of nature than a woman, and like with any natural disaster coverage, it’s impossible for witnesses to tear their eyes away.

FOUR

The Revenant by Michael Punke

Nothing you could possibly do will be as cool as an early 19th Century trapper extraordinaire/pirate/Pawnee hunter/frontiersman demigod surviving a bear mauling for the sole purpose of seeking revenge on those who wronged him. Get ready to feel entirely depressed and inferior while reading Michael Punke’s 2002 historical fiction The Revenant. The story of Hugh Glass’s battle against a grizzly, nearly mortal wounds, and extreme odds is actually a true one. With a few embellishments from Michael Punke, author of a handful of historical nonfiction books, the story practically writes itself.

THREE

The Martian by Andy Weir

In The Martian, Mark Watney is the only human being on an unforgiving, primarily dead planet and must use every ounce of his human ingenuity and resilience to find a way to survive with limited amounts of Earth’s luxuries. Nothing fancy, you know. Just the usual food, water, and air. Silly stuff like that. As NASA scrambles to send a rescue mission to a stranded astronaut, Mark Watney uses his scrappy resourcefulness, will to live, and dark humor to guide him through one of the most entertaining survival novels of our time. Andy Weir’s debut shines as a thrilling, accessible science fiction story.

TWO

To Build a Fire and Other Stories by Jack London

The title story to this collection of Jack London’s classic short stories is as dark and robust as any of the full novels on this list. A nameless man travels through the Yukon with his wolf-dog. When the dog falls through the ice, the man dives in to save his companion. Now, wet and freezing in temperatures of fifty below, the man is focused on a single, life-saving task: building a fire. London’s steady, descriptive prose mirrors the Nature’s indifferent temperament in the face of a human being’s impending doom. Sounds fun, right? Don’t forget to pack those weatherproof matches the next time you go camping, is all I have to say.

ONE

In the Heart of the Sea by Nathaniel Philbrick

Certain events in human history become something more than just a popular story or a factoid in a text book. Some events become growing, breathing, pulsing legends that inspire a nation, a world, a host of writers and filmmakers. This is the story of a whale that rejected its role as the prey of men, and the story of men who refused to sink under the brutal forces of the elements. In the nonfiction history In the Heart of the Sea, Nathaniel Philbrick tells the true and epic tale of the survivors of the Essex and their battle against an angry whale and the deadly indifference of nature. Frail humanity versus the open and indifferent sea? No thank you, but this–the most harrowing fight for survival–puts In the Heart of the Sea at the top of this list.

What are your favorite survival books? Leave me recommendations in the comments below!

![Serena [2008] by Ron Rash](https://litbeetle.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/serena-cover.jpg?w=318&h=474)

![In the Heart of the Sea [2000] by Nathaniel Philbrick (Photo from Wikipedia)](https://litbeetle.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/in_the_heart_of_the_sea_-_book_cover.jpg?w=432&h=646)

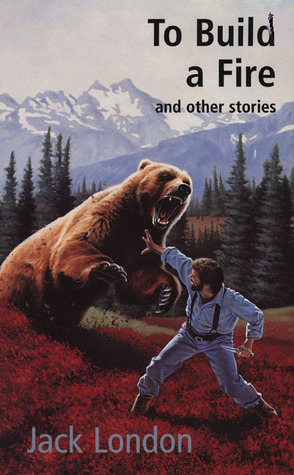

![The Buried Giant [2015] by Kazuo Ishiguro](https://litbeetle.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/the-buried-giant.jpg?w=290&h=436)

![The Sun Also Rises [1927] by Ernest Hemingway paints a portrait of the Lost Generation--namely, a group of ex-patriots surviving the Modern Age through willpower, irony, and a whole lot of wine.](https://litbeetle.files.wordpress.com/2014/06/the-sun-also-rises.jpg?w=335&h=509)