![The Buried Giant [2015] by Kazuo Ishiguro](https://litbeetle.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/the-buried-giant.jpg?w=290&h=436)

The Buried Giant [2015] by Kazuo Ishiguro

Ishiguro’s long-awaited seventh novel is not the traditional fantasy in the stereotypical sense of the label: unpronounceable made-up words, valiant heroes coming of age, and a fabricated back story longer than could fit in the 1,200 pages of the published product. Ishiguro’s fantasy is, in a handful of ways, much like his other novels: poignantly brief and excruciatingly sorrowful. The Buried Giant begins in a nameless hamlet in England. King Arthur is dead, and the England he united by sword and by law lies in an uneasy balance of Saxon and Briton. The people also lie under the spell of a heavy mist that suppresses the memories–both good and bad–of everyone it touches. The loss of memory transforms everyone into addled, helpless fools. People hunt for a missing child and then forget why they’re wandering through the woods. They set off down a road and 50 yards later can’t remember where they’re headed. Two elderly villagers, Axl and Beatrice, feel the nagging shade of a memory of a son they once had, and they set off to find him, in spite of their frailty and their foggy minds.

The English countryside is covered in a deep mist of forgetting. (Photo from “Carl Jones“)

Traveling from their small village, through cursed woods, over craggy mountains, toward their son’s village, the couple encounters a whole cast of references from Arthurian legend (half of which I’m sure I don’t even get). An ancient and doddering Sir Gawain quests with his equally ancient horse Horace to slay the she-dragon Querig who lives on top of the mountain. A young Saxon warrior quests to do the same, and when he crosses paths with our Axl and Beatrice, the couple is caught up in a story that will test the strength of their love as well as their memory. Before the wild world tears them apart from each, Axl and Beatrice must remember what they mean to one another.

One’s own memory is tricksy enough as it is, but when the topic of collective memory is addressed, history becomes a living entity unto its own. Think of how a nation or a society or even a family develops a collective memory through the retelling of an event or through the media or through trending, crowd-sourced narratives. We are constantly building our story as a group. When the mists of forgetting fall on the people of this story, ties are severed between present and past, between husband and wife. Beatrice is tormented with the idea of an incomplete memory, especially the memories of her son, whose name neither she nor Axl can recall. She and Axl have the opportunity to try and lift the curse, but is it worth remembering the pain of the bad memories just to experience the balm of the good ones?

Axl and Beatrice face many tests throughout their journey. Can they pass the ultimate test by proving their love to the boatman? (Photo from “Swaminathan“)

Ishiguro returns again and again to the concept of collective memory in his novels. In The Remains of the Day, especially, he discusses denial and misremembering through an aging butler struggling with memories of his involvement in dark deeds during World War II. The Buried Giant takes advantage of its fantasy genre to make the conversation of memory more blatant by making it more magical. Querig’s cursed breath descends on the land and forces a loss of collective memory for an entire generation. The horrors of that past are veiled in blissful forgetfulness, and the joys of a lifetime are only glimpsed in the corner of a dream. Ishiguro calls out humanity’s tendency to bury great tragedies to spare itself the pain and struggle of resolution. The collateral damage of this denial is that great joys and great accomplishments are also buried. Great loves and great progress are lost beneath the earth. Axl and Beatrice’s quest to find their son becomes a quest to remember–their son, their past, and their love for each other. In this beautiful novel that is at once lighthearted and tragic, Ishiguro produces a stunning story that is worth every moment of the ten years we waited for it.

“It would be the saddest thing to me, princess. To walk separately from you, when the ground will let us go as we always did.”

Read It: You don’t need to be a fan of Game of Thrones to enjoy this fantasy novel. In The Buried Giant, Kazuo Ishiguro addresses one of his favorite topics: the discrepancies of memory. The fantasy setting is a thin veil for the author’s deeply moving story about the fluidity of narrative, but it is also a deeply moving story, so whether your a scholar coming to study a contemporary master’s work or a casual reader like myself, just looking for an entertaining and skillfully rendered tale of adventure, look no farther than TBG.

Don’t Read It: You may not want to read this novel if dragons killed your parents or you have some blood feud with your Saxon neighbors. This novel doesn’t pull any punches when discussing the fiery political climate of the post-Arthurian era. Then again, and more likely, you may be expecting the Ishiguro of ten years ago, the Ishiguro of The Remains of the Day, and you’ll probably be disappointed. Gone is the subtler artifice of his earlier years, and if you don’t keep an open mind, his new style will turn you off, marvelous though it is.

Similar Books: I honestly can’t compare this novel to Ishiguro’s others, but if this is your first of his novels, please read The Remains of the Day to feel the power of his prose when Ishiguro reached what some would call the pinnacle of his literary career. Aside from this, The Buried Giant reminded me of classical epics like Virgil’s The Aeneid and Homer’s The Odyssey. Axl and Beatrice’s travels through the English countryside ring of older tales–tales of hellish paths and overcoming otherworldly challenges. For more reading on modern takes of Arthurian legend, read John Steinbeck’s The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights.

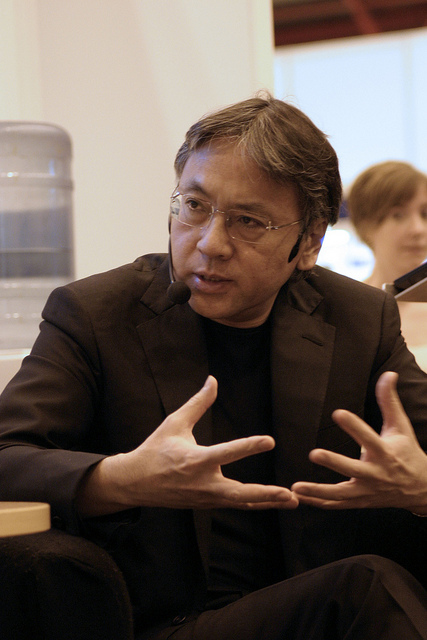

Kazuo Ishiguro (Photo from “English PEN“)

![Sarah Vowell's The Wordy Shipmates [2008] tells a very different story of the foundation of current day American than the one we're accustomed to hearing.](https://litbeetle.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/wordy-shipmates.jpg?w=197&h=300)

![Susanna Clarke's Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell [2003] won the Hugo, was nominated for the Nebula, and was named Time's best novel of the year. It's no joke.](https://litbeetle.files.wordpress.com/2014/06/jonathan_strange_and_mr_norrell_cover.jpg?w=199&h=300)